I have a meeting of sorts with a man I greatly admire. Many years before while studying at the School for Oriental and African studies, I heard of this man—a Hungarian who walked from Europe to India in search of his ancestors. Individuals who set off on cross-continental sojourns to check out their ancestral roots—these are the kind of folk I like to meet in my own travels. Indeed this Hungarian, who happened to become the first translator of Tibetan Buddhism to the West, would be one such character I would like to meet. Not because of the superior intellect he exhibited, although I deeply admire his ability to master in the course of his life not only Tibetan but seventeen other languages. Rather, I am drawn to this bold Hungarian’s sense of solitude, and the purity with which he travelled. He was a traveller in the truest sense—one who leaves home with no thought of returning. Travelling with no need ever to return brings a kind of inner strength. This strength comes from knowing one is ultimately completely alone in the world in which one travels. And for these travellers the movement of travel itself brings with it the deepest solitude—a solitude that does not mean having to be alone. This Hungarian, who left his Transylvanian home and never returned, dying in Darjeeling, never came to Japan. But this winter day I find myself searching for him in Tokyo…

I have a meeting of sorts with a man I greatly admire. Many years before while studying at the School for Oriental and African studies, I heard of this man—a Hungarian who walked from Europe to India in search of his ancestors. Individuals who set off on cross-continental sojourns to check out their ancestral roots—these are the kind of folk I like to meet in my own travels. Indeed this Hungarian, who happened to become the first translator of Tibetan Buddhism to the West, would be one such character I would like to meet. Not because of the superior intellect he exhibited, although I deeply admire his ability to master in the course of his life not only Tibetan but seventeen other languages. Rather, I am drawn to this bold Hungarian’s sense of solitude, and the purity with which he travelled. He was a traveller in the truest sense—one who leaves home with no thought of returning. Travelling with no need ever to return brings a kind of inner strength. This strength comes from knowing one is ultimately completely alone in the world in which one travels. And for these travellers the movement of travel itself brings with it the deepest solitude—a solitude that does not mean having to be alone. This Hungarian, who left his Transylvanian home and never returned, dying in Darjeeling, never came to Japan. But this winter day I find myself searching for him in Tokyo…Back in February 1819, it appeared as if Alexander Csoma de Kőrösi was going for a chilly mid-morning stroll along the riverbanks of his Hungarian village.

A bit of dark rye bread and cheese in the leather satchel and walking staff in hand, Csoma de Kőrösi certainly did not appear to be setting off from his homeland in search of the origins of the Hungarian race. Certainly if one wants to learn about one’s heritage, one may venture to the local university library for the afternoon, or perhaps just to the local café to ask a few old timers about grandpa’s grandpa—but, such a local, perusal approach was the antithesis of that taken by Csoma de Kőrösi. He felt no boundaries when travelling and left no query unanswered in his research.

A bit of dark rye bread and cheese in the leather satchel and walking staff in hand, Csoma de Kőrösi certainly did not appear to be setting off from his homeland in search of the origins of the Hungarian race. Certainly if one wants to learn about one’s heritage, one may venture to the local university library for the afternoon, or perhaps just to the local café to ask a few old timers about grandpa’s grandpa—but, such a local, perusal approach was the antithesis of that taken by Csoma de Kőrösi. He felt no boundaries when travelling and left no query unanswered in his research.We have to admire Csoma de Kőrösi’s ambition. At the time of his departure in February 1819, his only geographical reference for the goal of setting foot in his ancestral homeland was a chance classroom remark he had heard in his Gottingen University years before. Theologian and orientalist J.G. Eichhorn had mentioned in a lecture how “certain Arabic manuscripts which must contain very important information regarding the history of the Middle Ages and of the origins of the Hungarian nation are still in Asia.” Vague as it sounds, this was all the encouragement Csoma de Kőrösi needed to begin studying Arabic and tracking down maps in the dusty cartography department.

Later, during his studies of Arabic in Germany, Csoma de Kőrösi came across a work by the 7th century Greek historian Theophylact Simocatta that claimed the Turks defeated in 597 a people known as the Ugars.

Because of the linguistic similarity of the word Ugars to Ugor, Ungri, Hungar and Hongrois, it was thought by Csoma de Kőrösi and others that the Ugars could be a long-forgotten tribe who were likely ancestors of the present day Hungarians. Some histories Csoma de Kőrösi studied also erroneously tied the Huns and a people in Central Asia known variously as Ouars, Oigurs, or Yugras. These were the putative theories which led Csoma de Kőrösi to believe that his Hungarian ancestors were to be found in the Tarim Basin in Central Asian, very likely among the present day Uigyurs in East Turkistan (Chinese: Xingjian).

Because of the linguistic similarity of the word Ugars to Ugor, Ungri, Hungar and Hongrois, it was thought by Csoma de Kőrösi and others that the Ugars could be a long-forgotten tribe who were likely ancestors of the present day Hungarians. Some histories Csoma de Kőrösi studied also erroneously tied the Huns and a people in Central Asia known variously as Ouars, Oigurs, or Yugras. These were the putative theories which led Csoma de Kőrösi to believe that his Hungarian ancestors were to be found in the Tarim Basin in Central Asian, very likely among the present day Uigyurs in East Turkistan (Chinese: Xingjian).So it was that on 20 February 1819 Csoma de Kőrösi set out on foot to China via Moscow, intending to enter East Turkistan from the north. Count Teleky met Csoma de Kőrösi on the road that morning and asked him where he was going. Pausing briefly, a truly beatific Csoma de Kőrösi replied unambiguously, “I am going to Asia in search of our relatives.”

The first I heard of Alexander Csoma de Kőrösi was from Professor Piatagorski, an eccentric Russian lecturer of Indian Philosophy at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

I suppose Professor Piatagorski was fond of Csoma de Kőrösi because of their comparable mad brilliance, and similarities in their respective efforts involving painstakingly exhaustive research.

I suppose Professor Piatagorski was fond of Csoma de Kőrösi because of their comparable mad brilliance, and similarities in their respective efforts involving painstakingly exhaustive research. Dr. Piatagorski mentioned that Csoma de Kőrösi, in his life-long search for the origins of the Hungarian race, was the godfather to all current day translators of Tibet’s tantric literature. And, it was through Csoma de Kőrösi writings on the Kalachakra tantra that the West first learned of the mythical land of Shambhala. But in fact, translating tantric Tibetan texts was only a side project, a support, for the Hungarian who never wavered from the goal of finding the origins of his ancestors.

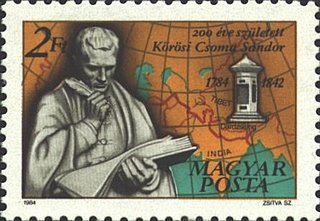

The final word I remember from Dr. Piatagorski on Csoma de Kőrösi hinted at a unique statue of the Hungarian in meditation posture somewhere in Japan. Dr. Piatagorski said the statue was called ‘Choma in the aspect of a Bodhisattva’, and chuckled, it was “as if the Hungarian chap was immersed in the contemplation of the vast cosmology of the Kalachakra, or tired there from…”

Csoma de Kőrösi’s travel plans changed as soon as he left Hungary. He never made it to Russia, nor to China. Instead, after stopping in Croatia to study Slavic and perfect his Turkish (adding to his linguistic rucksack which already included Latin, Greek, Hebrew, German, French, English and Romanian), he moved onto Constantinople from where he hoped to head north to Moscow. Because of an outbreak of the plague, he turned south instead by ship to Egypt and then to Syria.

Desert trekking to Mosul, he caught a boat down the Tigris to Baghdad where he continued alongside camels in a caravan to Tehran. In a letter from Tehran, Csoma de Kőrösi prophetically described his life’s journey, “Both to satisfy my desire, and to prove my gratitude and love for my nation, I have set off, and must search for the origin of my nation according to the lights which I have kindled in Germany, avoiding neither dangers that may perhaps occur, nor the distance I may have to travel.”

Desert trekking to Mosul, he caught a boat down the Tigris to Baghdad where he continued alongside camels in a caravan to Tehran. In a letter from Tehran, Csoma de Kőrösi prophetically described his life’s journey, “Both to satisfy my desire, and to prove my gratitude and love for my nation, I have set off, and must search for the origin of my nation according to the lights which I have kindled in Germany, avoiding neither dangers that may perhaps occur, nor the distance I may have to travel.”During the next three years of solo travel for this European Christian along the Silk Road—from the middle east to Bukhara, past the Bamian Buddhas and Kabul, and into Pakistan and Lahore—Csoma de Kőrösi changed his appearance and dress, spoken tongue, name and identification papers to suit, and indeed, survive the notoriously dangerous roads.

Having passed through Srinagar and Amritsar in 1823, Csoma de Kőrösi walked into the walled fortresses of Leh, the capital of Ladakh. Learning that his only option north to East Turkistan would be to go where no other westerner had ever been before—that is, trek over the 18,000-foot mountain passes of the Karakorum and Kun Lun mountain ranges.

Csoma de Kőrösi decided to turn back to Srinagar. It was a choice that led Csoma de Kőrösi not to East Turkistan, the assumed home of the Hungarians, but rather to an encounter with the seminal Great Gamer, William Moorcroft.

Csoma de Kőrösi decided to turn back to Srinagar. It was a choice that led Csoma de Kőrösi not to East Turkistan, the assumed home of the Hungarians, but rather to an encounter with the seminal Great Gamer, William Moorcroft.Moorcroft, a horse-breeder turned voyager turned spy, immediately took to Csoma de Kőrösi and he knew that British intelligence agents in Simla would have plenty of work for a linguist of Csoma de Kőrösi’s calibre—especially given the need to translate confiscated correspondence from Russian and other languages in which the Hungarian could work.

The only existing European dictionary of Tibetan at that time was the Alphabetum Tibetanum, published in Rome in 1762 after the work of A. A. Geeorgi, a Capuchin friar. With the Great Game in full swing, and the British at a loss for Tibetan speakers, Moorcroft and the East India Company offered to pay Csoma de Kőrösi to prepare a Tibetan dictionary.

The only existing European dictionary of Tibetan at that time was the Alphabetum Tibetanum, published in Rome in 1762 after the work of A. A. Geeorgi, a Capuchin friar. With the Great Game in full swing, and the British at a loss for Tibetan speakers, Moorcroft and the East India Company offered to pay Csoma de Kőrösi to prepare a Tibetan dictionary. Moorcroft was part of a handful of British imperialists connected to the East India Trading Company who can in large part be credited with the recovery of India’s architectural history of Buddhism. They were mostly young men who excelled in linguistics, archaeology, and downing stiff scotch—they were not the type of colonialists who sat around in their Raj tea gardens, they preferred traipsing through the jungle.

Lighting candles at Dhanyakataka Stupa at Amaravati on full moon

Lighting candles at Dhanyakataka Stupa at Amaravati on full moonThree months ago, I found myself at Amaravati, one such historically significant Buddhist site ‘re-discovered’ in Andhra Pradesh by Colonel Colin Mackenzie in 1797. I had joined over 200,000 other pilgrims for the Kalachakra initiation by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Significantly, Amaravati’s great stupa of Dhanyakataka is said by most sources to be the first place the Buddha taught the Kalachakra tantra. Csoma de Kőrösi noted in his textual research that a highly accomplished 99-year old tantrika by the name of Suchindra travelled from Shambhala to Amaravati where he was taught the Kalachakra by the Buddha—about 2,530 years ago. Thereafter, Suchindra returned to Shambhala, celebrated by his pious devotees as a great Dharma King, and passed on the holy teachings. So began the unbroken lineage of Dharma Kings who are still enthroned in Shambhala today.

Translating the deeds of benevolent Shambhalic kings ruling over esoteric lands of realized meditators and multi-faced deities was still only a secondary task—Csoma de Kőrösi was after hard logistics to plot the map to his homeland. Thus he continued the ardent task of cracking more codes to unlock the door to the origins of the Hungarians. And so, Csoma de Kőrösi spent the next eleven years engaged in Tibetan studies, living the life of a hermit with ascetic-like discipline. His efforts led to the publishing in the mid 1830s of his Tibetan dictionary, a grammar, and short accounts of Tibetan literature and history. In particular, using the ancient woodblock at Yangla monastery in Ladakh, Csoma de Kőrösi outlined the basic themes of the Kalachakra tantra and the Kingdom of Shambhala. His research on the Kalachakra represented the totality of westerners’ knowledge of the subject for nearly a century.

One night whilst studying in his room in Ladakh, Csoma de Kőrösi discovered a passage in a commentary on the Kalachakra tantra that he believed not only pinpointed his ancestral homeland, but also identified it as none other than Shambhala, which he portrays as ‘the Buddhist Jerusalem’.

Csoma de Kőrösi wrote, “the mentioning of a great desert of twenties days’ journey, and of white sandy plains on both sides of the Sita, render it probable that the Buddhist Jerusalem (I so call it), in the most ancient times, must have been beyond the Jaxartes [in current day Uzbekistan], and probably the land of the Yugurs.” Csoma de Kőrösi believed that the Kalachakra tantra was his esoteric passport to his native soil in East Turkistan. Csoma de Kőrösi was not of the view that the Shambhala he was studying was a description of an imaginary landscape, a contemplative playground, or some sort of passageway to a Buddhist metaphor—he believed literally that these tantric scriptures gave the latitude and longitude markings for Shambhala, which was none other than the land of the Yugurs, or Uigyurs, from which flowed his ancestral lineage.

Csoma de Kőrösi wrote, “the mentioning of a great desert of twenties days’ journey, and of white sandy plains on both sides of the Sita, render it probable that the Buddhist Jerusalem (I so call it), in the most ancient times, must have been beyond the Jaxartes [in current day Uzbekistan], and probably the land of the Yugurs.” Csoma de Kőrösi believed that the Kalachakra tantra was his esoteric passport to his native soil in East Turkistan. Csoma de Kőrösi was not of the view that the Shambhala he was studying was a description of an imaginary landscape, a contemplative playground, or some sort of passageway to a Buddhist metaphor—he believed literally that these tantric scriptures gave the latitude and longitude markings for Shambhala, which was none other than the land of the Yugurs, or Uigyurs, from which flowed his ancestral lineage. Upon completion in 1837 of the dictionary and grammar, Csoma de Kőrösi decided to remain in India to continue his study of Sanskrit and related dialects, still preparing himself linguistically for his journey via Lhasa to his believed homeland to the north.

Csoma de Kőrösi felt further study of Sanskrit was the key needed to open the meaning of many of the scriptures found in the great monastic libraries in Lhasa—which would provide further clues to the ancient Uigyur Kingdom. By this time, Csoma de Kőrösi had mastered eighteen languages, and while Tibetan was in his repertoire, he still had not set foot in Tibet proper—although Ladakh is often included geo-culturally as Western Tibet.

Csoma de Kőrösi felt further study of Sanskrit was the key needed to open the meaning of many of the scriptures found in the great monastic libraries in Lhasa—which would provide further clues to the ancient Uigyur Kingdom. By this time, Csoma de Kőrösi had mastered eighteen languages, and while Tibetan was in his repertoire, he still had not set foot in Tibet proper—although Ladakh is often included geo-culturally as Western Tibet. In late March 1842, Csoma de Kőrösi made his way from Calcutta, still on foot, through the Terai jungle to the hill stations in Darjeeling. He immediately forged relationships with Dr. Archibald Campbell, a British agent based in Darjeeling. The diplomat set up the diplomatic necessities enabling Csoma de Kőrösi to travel through Tibet. But his journey through the jungle had taken its toll and by the first week of April, Csoma de Kőrösi was running a high marsh fever, likely malaria. Dr. Campbell wrote of Csoma de Kőrösi, “…all his hopes of attaining the object of the long and laborious search were centred in the discovery of the country of the ‘Yoogors’…to reach it was the goal of this most ardent wishes, and there he fully expected to find the tribes he had hitherto sought in vain.”

On 11 April 1842, Csoma de Kőrösi died peacefully. Campbell noted that the Hungarian’s only possessions were, “four boxes of books and paper, the suit of blue clothes he always wore, and in which he died, a few sheets, and one cooking pot.”

Csoma de Kőrösi’s journey wanders through my mind as I stare at him wrapped in his meditation shawl, hands resting in his lap. This twenty centimetre bronze statue, with his sorrowful downcast eyes, speaks volumes—of a quest for knowledge, of journeys into the unknown, and of the stark reality that death may come at any moment. It may seem tragic that Csoma de Kőrösi’s pursuit to reach East Turkistan, land of the Uigyurs, was off the mark, that it was not the ancestral homeland he believed. Still, it is indeed admirable to bear witness to such a devoted quest of this solitary traveller—and it would seem that Csoma de Kőrösi quest for his Shambhala was a life well spent.

19 February 2006 Tokyo, Japan

Photo caption: The Japanese named the 20 centimetre bronze statue simply, “Choma in the aspect of Bodhisattva”, after it was gifted to the then Imperial Museum in 1931 by Hungarian journalist, Dr. Felix Va’lyi.

2 comments:

excellent

if you're 35, i'm 21!!!! you maniac!

Post a Comment