When I find you again,

it will be in the mountains;

this morning, I lose you

once more to farewell.

Free of attachment

in heart and mind—

is why you can go

Ten thousand miles alone

to places with such

little human warmth,

where, when you meet someone,

they speak an ancient tongue?

Traveling without disciples,

you have only

a white dog

for company..............

.........But this week, we are in southwest France…

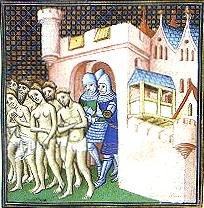

François Montes is a white-haired charcoal sketch artist who lives within the granite stone walled village of La Couvertoirade. Walking around the four sentinel towers of this ancient town takes less than twenty minutes. Within the thirty or so stone houses including Francois’ small two room drawing guild, single Church, and a few wine cellars, most of the towns’ residences fell to the swords of the marching Crusaders in the early 1200s. The crusaders arrived on Pope Innocent the III’s order to root out this strong bastion of a heretical religion in similar small towns and fortress like La Couvertoirade. The heretics were the Cathars. However, François was not too bothered to explain any of this when we sat down next to him and his white poodle. In fact, he did not bother to look up, as he was content playing a bluegrass-sounding ditty on an oddly shaped 6-string zither instrument, the épinette.

This small village of La Couvertoirade sits in the middle of the southwestern French region known as Languedoc. Historically, the boundaries of Languedoc were marked by the Occitan language (langue d’Oc). Occitan was the lingua franca that flourished during the Middle Ages along the Mediterranean from the foothills of the Spanish Pyrenees to the Italian Alps, and spreading north towards Savory and west along the Atlantic coast. In this’ corner of Languedoc, the landscape is as dramatic as its history. From the coastal area around the Mediterranean Gulf de Lyon, to the arid limestone plateau where Lerab Ling and Francois’ small village are found to the huge river gorges and completely depopulated areas of the Causses, to the rugged Cévennes mountains, it has rough quality to it. For centuries, much of the area off of the coast was impenetrable, and even now it retains something of an air of mystery. Near the coast, however, you will find the lazy hills hosting as far as the eye can see fields that produce the local wine and olives.

It was in the harsh inland environment of the hills and plateaus, where most inhabitants lived in fortified towns that the Cathar religion flourished. Catharism was a variant on ancient Persian beliefs combined with Christianity; a dualistic creed which portrayed the material world as an invasion into the realm of Light by the powers of Darkness—sounds like Star Wars but for sure there was more killing taking place here than in any George Lucas film. Propagated by men dissatisfied with the indulgent Catholic bishops and clergy, the Cathars were lead by those who took vows of poverty and tried to emulate the austere Apostles of Christ. Catharism believes that God reigns over the spiritual world, the Devil created all matter, and Christ was God’s messenger through whom human souls could be united with the Divine and attain immortality. This belief posed a number of problems for the Roman Catholic Church. Firstly, Cathars denied the doctrine of the Virgin Birth, and insisted that the Catholic faithful, in worshiping any Creator (of matter), were in fact worshiping the Devil. They were immaterialists by definition and asceticism was seen as the only pathway to redemption. They were also pacifists who condemned the Crusades.

After his election to in 1198, Pope Innocent the III began to pressure the local nobility in this region to reign in the

heretical Cathars and bring them back into the Catholic fold (Dominican and Franciscan preaching friars had already failed in their efforts some years before). When the papal legate in the area called a meeting with the previously excommunicated, but still popular Cathar Raymond VI of Toulouse, an argument broke out and Raymond sent the pope’s representative’s head rolling—literally—with a swing of his sword. When news got back to the Innocent the III, a crusade was called—the Albigensian Crusade—against the Cathars. The seasoned crusader Simon de Montfort, and powerful Cistercians monastics turned swashbuckling monks arrived in waves over the next 15 years in various attempts to root out Catharism, and in return getting their loot and booty. In 1209, an army led by the archbishop of Narbonne and the papal legate Arnaud Amaury invaded Languedoc, with a heavy contingent of English mercenaries in its ranks.

heretical Cathars and bring them back into the Catholic fold (Dominican and Franciscan preaching friars had already failed in their efforts some years before). When the papal legate in the area called a meeting with the previously excommunicated, but still popular Cathar Raymond VI of Toulouse, an argument broke out and Raymond sent the pope’s representative’s head rolling—literally—with a swing of his sword. When news got back to the Innocent the III, a crusade was called—the Albigensian Crusade—against the Cathars. The seasoned crusader Simon de Montfort, and powerful Cistercians monastics turned swashbuckling monks arrived in waves over the next 15 years in various attempts to root out Catharism, and in return getting their loot and booty. In 1209, an army led by the archbishop of Narbonne and the papal legate Arnaud Amaury invaded Languedoc, with a heavy contingent of English mercenaries in its ranks.  At the city of Béziers, local Catholics refused to reveal to the pope’s representative who amongst their own still held secretly onto their Cathar beliefs. In true Crusader style, the city was besieged and its entire population—numbering over 20,000—was massacred. When asked how the Catholic citizens were to be distinguished from the heretics, Amaury replied, “Kill them all, God will recognize his own.”

At the city of Béziers, local Catholics refused to reveal to the pope’s representative who amongst their own still held secretly onto their Cathar beliefs. In true Crusader style, the city was besieged and its entire population—numbering over 20,000—was massacred. When asked how the Catholic citizens were to be distinguished from the heretics, Amaury replied, “Kill them all, God will recognize his own.” The final chapter to the Cathars was played out in the mid 13th century when the infamous Inquisition burned at the stake the last believed 225 Cathar in a mass pyre at Mirepoix. Yet, four Cathars are said to have escaped the heat and took with them the Cathar ‘treasure’ from a nearby cave, which some in this area believe was in fact nothing other than the Holy Grail, and the Cathars themselves were the true Knights of the Round Table.

As I was studying this Cathar belief system and history, François kept playing his zither while his white poodle ran around our feet.

After the second cup of coffee, I mentioned to François that his music sounded like country bluegrass. His 70-year old eyes lit up and said with the strongest French accent available in Languedoc, ‘Mais, tu connais Granpa Jones—But, you know of Grandpa Jones?’ Kinder spirits uniting under the banner of bluegrass, we were both feeling like brothers. ‘Le bluegrass vient veraiment du coeur—Bluegrass music is truly from the heart,’ he exclaimed. He spent the next two hours alternating between explaining the history of his (originally Norwegian) string instrument, giving me a few lessons, and even breaking out his 1979 special tape recorder and playing along with some authentic Grandpa Jones and Frank Stanely from the album, “Let Me Rest On A Peaceful Mountain.”

After the second cup of coffee, I mentioned to François that his music sounded like country bluegrass. His 70-year old eyes lit up and said with the strongest French accent available in Languedoc, ‘Mais, tu connais Granpa Jones—But, you know of Grandpa Jones?’ Kinder spirits uniting under the banner of bluegrass, we were both feeling like brothers. ‘Le bluegrass vient veraiment du coeur—Bluegrass music is truly from the heart,’ he exclaimed. He spent the next two hours alternating between explaining the history of his (originally Norwegian) string instrument, giving me a few lessons, and even breaking out his 1979 special tape recorder and playing along with some authentic Grandpa Jones and Frank Stanely from the album, “Let Me Rest On A Peaceful Mountain.” As we approached mid-day, it was time to take our leave but not before François decided I should have my own 6-string Norwegian zither at home. Taking me into his guild, he covered his leather fingers with black charcoal. Then, laying out a beige paper over the épinette, he rubbed his musical instrument, taking particular care to note the spacing of the frets as this gives the distinctive three-octave scale for the instrument. Handing me the charcoal tracing, he instructed me what kind of wood to use for the top and sides, and then said, ‘now that you have had your first lesson, go back and make your own épinette, and then return for another lesson.’

Chia Tao also wrote in the 8th century:

Not having to be alone

is happiness;

we do not talk

of failure or success.

No comments:

Post a Comment