Gendun Rinchen's Birthplace

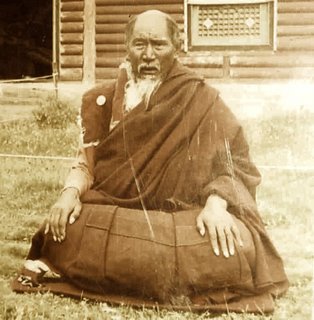

On April 18, 1997, the ailing Bhutanese meditation master, Gendun Rinchen, whispered to his attendant to help him sit up straight in his bed. His attendants then draped a yellow silken shawl over the old lama’s shoulders and stepped back. Gendun Rinchen’s eyes and mouth were slightly open as he placed his hands on his knees. His soft gaze extended into the space fixating on nothing in particular. Remaining upright in meditation posture with his body and eyes unmoving, aware of his imminent death, Gendun Rinchen breathed his last breath.

Extinguishing the single butter lamp and incense stick that were burning in the room, his attendant backed out of the room and immediately notified the Bhutanese royal palace and government that the former Je Khenpo, the senior most Buddhist teacher and ritual master of Bhutan, had died. Monasteries throughout Bhutan began elaborate death rituals on behalf of the 69th Je Khenpo that would last for the next 49 days, the maximum period it is believed before one takes rebirth.

Buddhist culture of the Himalayas suggest that the body of a deceased person should not be moved or disturbed whilst the process of death takes its course over a few days. It is believed that when one’s breathing stops, the process of death begins whereby the elements (air, water, fire, earth) that comprise one’s corporal body progressively dissolve. While the death process of the body is in course, the mind is in a kind of suspended state, ‘in-between’ death and the next rebirth. These in-between states tend to be very disturbing to the mind because of our very strong attachments in this (and past) lives to one’s body and physical world—something that is crumbling all around us at death. During this dissolution process, the mind finally takes leave from the body and is blown towards the next rebirth by the strongest of one’s karmic winds.

Accomplished meditation masters can remain in a meditative state while the elements dissolve, not being disturbed by the rather turbulent, but completely natural, dying of the body. Because of meditative training in the process of death before one dies, such masters can control when their mind departs their body. Furthermore, as their minds are not shaken by the seemingly volatile ‘in-between’ states of the death process, they are not unknowingly blown into their next rebirth by their karmic winds but rather, can control when and where they will be reborn.

A day after Gendun Rinchen had stopped breathing Bhutanese doctors trained in both traditional and allopathic medicine cautiously entered the room, not wanting to disturb the meditative equipoise of the lama. The doctors checked for vital signs of the old lama and while there was no respiratory or cardiovascular activity, the chest of the lamas was still warm to the touch. For a mediation master to remain for hours or even days in mediation after they have ‘died’ is not uncommon, so the doctors left the old lama to continue his meditation. The doctors informed the palace and government that Gendun Rinchen was in a meditative state is known as tukdum.

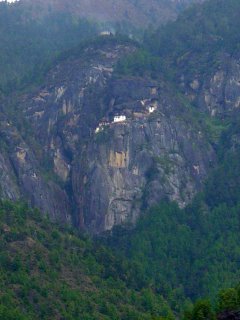

Gendun Rinchen was born in 1926. While still in the womb, his mother awoke on morning and felt the strong urge to visit the hermitage of Taksang, or Tiger’s Lair, the most holy place of Bhutan. Despite her advanced pregnancy, she walked up the steep ravine and steps that are cut into granite en route to the Tiger’s Lair.

Tiger’s Lair hermitage is located on the face of a sheer 1,000-meter cliff above Paro valley. In the 8th century, Padmasambhava, the tantric ascetic who established Buddhism throughout the Himalayans and on the Tibetan plateau, flew to Taksang from Khenpajong in northeast Bhutan on the back of a tigress in order to subdue demonic forces in the land. In this form, Padmasambhava was known as Dorje Drollo.

Before arriving at the small, ancient temple of Taksang, the young woman went into labour and Gendun Rinchen was born in the cave on the approach side of Tiger’s Lair. The young boy entered a monastery at a young age and went to eastern Bhutan at Nimalung Monastery in Bumthang to study the 13 Great Expository texts that included logic, debate, composition, poetry, medicine and astrology. Just before Chinese rule overran central Tibet, Gendun Rinchen was able to study in Lhasa specializing in Madhyamika (Middle Way) philosophy. His mastery over the 13 Expository Texts in Lhasa earned him the highest scholastic title of Geshe. Gendun Rinchen had left Bhutan an aspiring philosopher and returned to his homeland an erudite scholar and meditator who commanded enormous respect. It is said that when Bhutanese monks would go to teachers in Lhasa after Gendun Rinchen’s return to Bhutan, those Tibetan teachers would turn away the Bhutanese saying, “Return to your homeland where you can study with the great Geshe Chagpu Gendun Rinchen.”

After Gendun Rinchen returned to Bhutan, he entered a three-year retreat at the remote Tiger’s Lair hermitage, which was followed by another three years of retreat at Kuegacholing in Paro. For a decade thereafter, he was the abbot of Tango philosophical college where he wrote many commentaries on sutra and tantric topics, as well as philosophical expositions. His contributions to Bhutan’s literary heritage exceed 11 volumes, which included not only the aforementioned topics, but also historical volumes on Bhutan’s hereditary monarchs and Bhutanese saints.

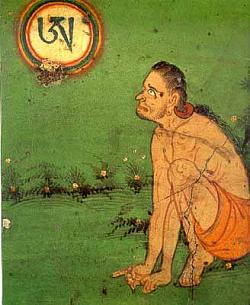

Taksang Hermitage Mural from Namkai Nyingpo Monastery

When the renowned meditation master Sonam Zangpo, the grandfather of the current Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, came to the Dugsta Lhakhang in Paro in1960s, he came across a philosophical discourse by Gendun Rinchen. Sonam Zangpo was struck by the similarities in tone and content to writings by Terton Sogyal Lerab Lingpa who Sonam Zangpo had met in Kham some decades before. Sonam Zangpo asked that Gendun Rinchen be brought to him and it is said at this time he recognized him as one of the three incarnations of Terton Sogyal. Sonam Zangpo’s recognition of Gendun Rinchen as an incarnation of Terton Sogyal was in fact in prophetic accordance with Terton Sogyal himself—that is, Terton Sogyal would take one of his rebirths near Tiger’s Lair hermitage in Bhutan.

Late in Gendun Rinchen’s life, the Bhutanese government recognized his scholarship and mastery of rituals gave him the title of Je Khenpo, the senior most Buddhist teacher in Bhutan. He held this position from March 1990 until May 1996 when he was given royal leave to retire to a life of prayer and meditation.

After more than a week in tukdum, Gendun Rinchen’s body still remained in upright meditation posture, although the warmth in his chest had left. As parts of his body had been warm for some days after he stopped breathing, doctors had decided not to treat the body with any medicinal ointments or salts. After the body had gone cold, monk attendants and doctors noted that there was no rigourmortous, decomposition or odour to the body. It was known that Gendun Rinchen was an accomplished meditator, but for his body to show such uncommon signs was something that was truly extraordinary. That his body, or kundung, was not decomposing but rather remaining in mediation posture well after his mind had departed was a sign that he had purified the very elements of his corporeal body through meditation.

Some years later, Gendun Rinchen’s body was taken from the house where he died and placed in a golden reliquary (chorten) in the Zhabdrung Temple in the Tashicho Palace in Thimphu. In addition to visiting the Tiger’s Lair and Longchempa’s seat in eastern Bhutan, I was intent on circumambulation of his enshrined body on this October 2005 pilgrimage to Bhutan.

Upon arrival at Paro airport, I picked up the national newspaper, Kuensel, and found the headline on the front-page reading, “Photograph dealers detained”. The story read:

“The Council for Religious Affairs handed over a monk who worked as the council’s official cameraman, Sangay, to the police on October 5 in connection with the illegal sale of a photograph of the late Je Khenpo Geshe Gendun Rinchen.”

“According to the Council’s spokesperson, the accused was asked to take a picture of the kundung of the 69th Je Khenpo fro the archives when the kundung was taken out of the Zhabdrung Lhakang on May 18.”

“The picture of the kundung was taken when the face was painted with gold before being installed in the Kundung Chorten.”

The newspaper reported that the monk had been warned not to show anyone the photograph yet, he ignored such advice and colluded with a Thimphu based photo shop and made over 30,000 copies to be sold. When I arrived in Bhutan, the Bhutanese authorities were on a gestapo-like hunt for 3,000 copies of the photo, as the other 27,000 had already been confiscated.

It seems that the authorities were more despondent that holy images of the Je Khenpo were being sold rather than the fact that people were devoted to the lama and his image. Devotion to Je Khenpo and his documented miraculous achievement of not having one’s body decompose not withstanding, the police wanted all of the photos returned and were on the streets in Thimphu, Trashigang, Bumthang and Paro looking for them.

My second night in Thimphu, I happened upon a shopkeeper in one of the dusty alleys who told me a few stories about Gendun Rinchen as she had met him. She mentioned in passing that she had come across one of the banned photographs in recent days and had devotedly placed it on her shrine in her home. To her disappointment, within a few days of our conversation, the man who had sold the photograph to her asked her to return it to him, on order of the police. Fortunately, I was able to have dinner at her family home and meet face to photographed-face with the Je Khenpo before the photograph was handed over.

Paro, Bhutan October 23, 2005

Travelling Matteo and the Crew

GOMCHEN

GOMCHEN